When feeding the world gets morally murky

The scientific savior complex and Vavilov's seed bank

"We made our oaths to Vavilov

We'd not betray the Solanum

The acres of Asteraceae

To our own pangs of starvation

When the war came, when the war came..."—The Decemberists

Plant scientists have a bit of a savior complex. We love to see ourselves as crusading heroes, working to create new knowledge, feeding the world, protecting the planet. Certainly, connecting to a broader societal goal is strongly motivating. However—and it’s hard to admit this—there are ways in which identifying so deeply with solving global challenges can blind us to the damage done by that same work. For example:

What does it mean to be developing crops resistant to climate change, if everyone in the field promotes their work by traveling on airplanes multiple times a month (and thereby contributing to global warming)?

Is research that aims to protect natural ecosystems truly helping if it creates trashcans full of plastic waste every week?

What if you collect and propagate seeds and tubers from ancient crops in order to promote food security in your country, then allow your neighbors to starve to death instead of distributing those seeds or potatoes?

The Leningrad seed bank

This last question might seem strangely specific, and few months ago I wouldn’t have known to include it. But I’ve been reading about seed banks for a book review (out in November, I’ll link here). I don’t mean natural seed banks, though those are extremely cool. This kind of seed bank (or seed vault) is, quite simply, a place where people store seeds for future use. One of the earliest and most famous international seed bank was built in Leningrad in the early decades of the 20th century. Vavilov believed that the ancestors of current crop plants held tremendous potential for genetic diversity that could be used when breeding new traits into crops.

This unique and valuable collection was put into extreme jeopardy in WWII, especially during the 900-day siege of Leningrad. The botanists working there protected the collection, and—amazingly— refrained from eating any of it, even as Leningrad starved around them (as many as 1/3 of its inhabitants died during this period), even as THEY starved. These brave seed bank scientists protected a resource that they saw as important for the future of their country, and paid with their lives. Their sacrifice has been captured in books, music, and film (see my list of resources below).

A plant biologist’s plant biologist

The director of the Institute at the time, Nikolai Vavilov, was beloved among botanists across the world. He and his team of scientists gathered hundreds of thousands of different kinds of seeds and tubers from at least 64 countries, on over 100 different expeditions. I’ve often seen him referred to as the “Indiana Jones of Botany”, in reference to his travels, and apparently, to a fedora he favored.

Vavilov trained with Bateson (who coined the term genetics), and worked for some time at the early John Innes Institute, applying the theory of Mendel towards improving crops. He was internationally celebrated for his sophisticated theories. But his approaches to plant breeding, now so accepted as to barely be taught, were challenged and dangerous to promote under Stalinism.

But not Stalin’s plant biologist

Ironically, it was a previous student of Vavilov, Trofim Lysenko, who was Vavilov’s worst enemy. Lysenko followed Lamarck’s theory that organisms could acquire traits during their lifetime; a theory that apparently resonated with Stalin because it meant that lineage doesn’t matter. Whether it was pointing out problems with traditional Soviet agricultural practices, or promoting Mendelian genetics, Vavilov was dangerous to the Stalinist cause. He was arrested in 1940 and died in prison in 1943.

The villains of the story

Vavilov’s death left his Leningrad team to protect the seed bank from multiple enemies: their own hunger, inevitable decay, the intense cold of the winter of 1940, the vermin that were starting to overrun Leningrad, and from its increasingly hungry and desperate people. The remaining scientists must have known that they were also protecting the collection from their own state, which had no respect for it. And they also must have known they were protecting it from Heinz Brücher, a Nazi plant breeder who viewed plant breeding and race theory as twin branches of genetics. Brücher traveled through the country during the German occupation, gathering as many seeds from Vavilov’s outposts as he could, and scheming on ways to get the main collection.

In the end, the majority of the seed and tuber collection survived.

It’s an incredible story. But I wonder (as did this author) if the story of Vavilov and his crew as heroes might be too simple. Yes, the botanists working for the Plant Institute protected their seed collection under some of the worst conditions imaginable. But they did so against direct orders to eat or distribute them. Especially given that the eventual outcome of the collection could not be known, was it appropriate for a small group of people to decide what to do with scientific resources like this, materials that could have saved the lives of many?

And Vavilov and his team weren’t exactly stealing, as they traveled around the world collecting seeds and gathering local information in collaboration with local growers—but there is a grey area here. There is an aspect of seed banking that looks kind of like seed hoarding.

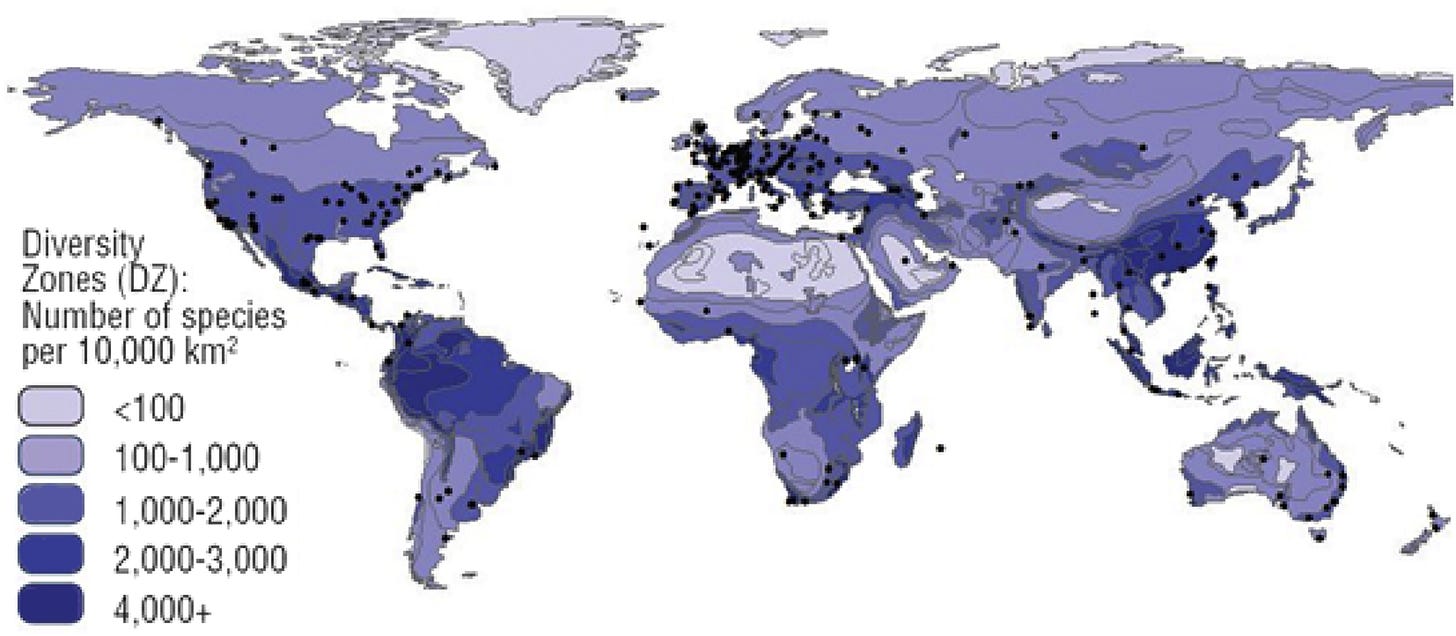

For example, check out the map below, taken from this article. The location of seed banking institutions (black dots) is disconnected from the location of most plant diversity (dark purple). Instead, seed banks are located in richer countries, mostly the US and Europe. In essence, resources for the future are removed from their location and stored in countries that already have more resources.

The authors call this “ex situ” banking. They acknowledge that it would be ideal for seeds to be collected and stored “in situ” but that this is not currently feasible:

“Ideally, seeds should be conserved in the country of origin so that they are easily available for restoration and reintroduction. However, many countries do not have the capacity to collect and store wild collected seeds.” —O’Donnell and Sharrock, 2017

Thus, they seem to argue, the countries that have more resources should be protecting seeds. But this only perpetuates inequality, and the same rationale has been used for centuries to loot artifacts and art from Egypt and many other countries. Museums are beginning to grapple with returning looted art to the cultures from which the pieces were stolen—is it is time for seed banks to do the same? As the authors of recent opinion paper on plant biology in the global south wrote:

“The systemic issue of historical and ongoing theft of plant material from the Global South perpetuates an unfair system that both disfavors and excludes the Global South research community. “ —Auge et al., 2024

Seed banking for everyone.

Furthermore, seed banking does not absolutely require large state-funded endeavors. I recently chatted with Gabriel Campbell, Director of the Rae Selling Berry Seed Bank at Portland State University. He reminded me that “people have been seed banking since we have been doing agriculture.” Anyone can store seeds.

The work of Vavilov and his team, and those working at other institutionalized seed banks is extremely important, and it’s true that the highly technical approaches used at Kew Gardens’ Millenium Seed Bank and Svalbard Global Seed Vault can’t be replicated everywhere. But they are run by just a few people and controlled by just a few countries, making them as precarious as the Leningrad seed bank was. Maybe the scientific heroes we need right now are those that enable the distributed protection and storage of seeds and other genetic resources, and leave control in the hands of the people and cultures to whom they belong.

Resources:

Writing a review of this book is what got me interested in these questions. It’s so good! I’ll link to the review here once it’s out.

I read the first few chapters of this book before I had to return it to the library, and now I want to read more from Gary Nabhan.

There is a 2019 film I’d love to see about the Vavilov seed bank.

Discussion Section

Scientists: do you see trade-offs in your research? How does this intersect with your motivation, and your ability to recruit trainees?

Non-scientists: is there a similar tension in your work? Maybe the concept of colonialized/decolonialized literature?

"Plant scientists have a bit of a savior complex."

I appreciate your attention to the moral dimension and unintended consequences of scientific research Liz. It makes me think of Norman Borlaug's development of "super grains". They were hailed as a boon to humanity, but by dramatically raising the "carrying capacity" of the planet, it triggered a massive increase in the human population. That has led to massive environmental destruction, climate disruption and incalculable species deaths. As always, science shows us what we can do, not necessarily what we should do.