As someone writing a memoir (and just generally trying to understand WTF I am doing here), I have been thinking a lot about personal narratives and how they are organized in the mind of the writer. I’m also a visual thinker, someone who thinks best when drawing diagrams, and lately I’ve gotten interested in the way we illustrate those personal narratives.

In Western literature, the most common shape for a narrative, whether memoir or fiction, is an “arc” that starts with a conflict, builds towards a climax, and ends with a resolution. This narrative structure is often diagrammed as a peak or an arc where the x-axis is position in the story and the y-axis is tension or action:

Down with the narrative arc!

In Meander, Spiral, Explode, Jane Alison suggests that relying so much on the narrative arc is limiting, and encourages writers to be open to other shapes:

“For centuries there’s been one path through fiction we’re most likely to travel― one we’re actually told to follow―and that’s the dramatic arc: a situation arises, grows tense, reaches a peak, subsides . . . But something that swells and tautens until climax, then collapses? Bit masculosexual, no?” J. Alison

I mean, I like this narrative shape, too—it is satisfying and feels complete. [Insert blushing emoji]. But, in memoir, it doesn’t always feel honest, and there are plenty of examples where writers seem to have forced their story into this shape (e.g. Glennon Doyle’s Love Warrior or, as Wendy Robinson writes, Rebecca Wolf’s Girls Gone Child blog) and then have to explain why their real lives don’t match the narrative they’ve sold.

Beyond the arc, but still on a Cartesian graph

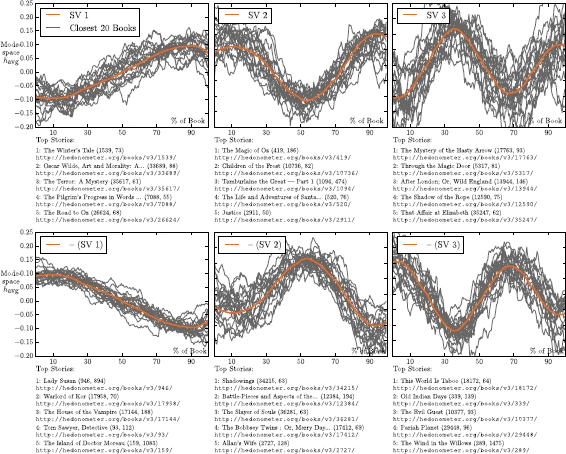

The arc describes a simple narrative, but even the most complex stories can be seen as involving a protagonist who moves forward in time and upward or downward according to some other parameter like wisdom or impact or personal connection. According to this paper, which used machine learning to analyze over 1,000 books in the English language, they all fall into just six basic shapes (which probably explains why so many movies and books feel similar):

What if Cartesian geometry doesn’t feel like the right way to describe your life’s path?

But how do you visualize your life story when it doesn’t feel like it follows an arc or arcs? When there is no linear, 2-dimensional path, when individual events don’t build to a climax? Are there other ways to structure a story, to frame our own experience that isn’t moving from point to point along an x-axis?? Jane Alison argues that yes—there are plenty of other shapes a story can take, and she takes her inspiration from nature.

“So many other patterns run through nature, tracing other deep motions in life. Why not draw on them, too?" J. Alison

She mentions fractals, spirals, branches, cells—all beautiful patterns found in plants that could be the basis for a narrative. As a plant person, I love this. I also think I need to be thinking outside the Cartesian box for understanding my own story. The more I write, the less comfortable I am with the idea that my life has any kind of linear path or that it’s moving in a particular direction. I certainly don’t believe that leaving academia was a hero’s journey.

What about cycle instead of a line?

Another pattern we see in nature (and of course in plants) is a cycle. Personal coach Molly Mahar has a framework for understanding our lives as repeated cycles rather than as a line. She says we move through four “years” in a particular order: growth, mastery, unrest, destruction and then back to growth. I think this concept is brilliant (and her Spotify playlists are pretty great too). In this post, she presents The Cycle of Years as a way to get away from comparison with others, but I find it generally freeing to imagine we are not moving towards a single final destination at the end of the x-axis, but that our lives are defined by stages that feed into each other and provide meaning all along the way.

As I reflect on the past few years, and as I struggle with acknowledging the accomplishments and recognizing the disappointments, Molly’s framing has been useful. No doubt, 2022 was a year of destruction. I quit my faculty position, we sold our condo in St. Louis, and my family moved across the country to Oregon without a plan other than to be closer to family and to a state safe for transgender youth. We upended our lives (and our finances) in so many ways!

I had expected 2023 to be a year of mastery, as I had several solid leads for a next position. And if you believe what you see on LinkedIn or The Professor is Out, many people jump right from academia to a fulfilling, well-paying high profile position. But, in the end, I did not—in fact it’s been a year and a half since I started looking, and I am still freelancing to help pay the bills. Looking for full time positions outside academia has been as hurtful and painful as anything that happened to me inside academia, and my sense of myself as a highly skilled person—something you’d think 15 years as a successful academic scientist would ensure—was pretty much destroyed.

But, according to Molly, you don’t go from destruction to mastery. You go from destruction to growth. And that feels right for 2023. I learned so much about writing this year, thanks to my kind and endlessly talented teachers Brian Benson and Erica Berry, to a fantastic class lead by Lily Dancyger, and from just reading so many wonderful and innovative writers. I am slowly growing out of the mindsets and habits that suited me so well to academia but were not truly healthy. And I’ve grown in other ways that just weren't possible when I was working so many hours.

What is next for me and for Unprofessoring in 2024?

While I’d love to predict that 2024 will be my year of mastery, I’m pretty sure there’s just more growth to come, on many fronts. Growth as we settle into life in Portland, strengthen new and old friendships, and find connection to communities and to the outside; growth as I learn more about the craft of writing by doing as much of it as I can manage; and growth as I figure out how to feel happy and fulfilled without the constant ego-boosts that came with being an established and successful academic scientist.

Speaking of growth to come, I have a few updates on the newsletter. You might have noticed that I didn’t post during December. I felt unable to write, and though I had tons of ideas, I wasn’t able to sit down and do the work of getting words into order. Any energy that I did have, I had to put towards the book-writing project. I think posting once a week—which I never was able to do for more than a few weeks at a time—is too much when I’m also working on the book and on freelance projects. So, in 2024 I’ll be dropping back to posting once every two weeks. I’m hoping that I can be a bit more consistent with this more relaxed schedule!

Thank you

As I look back over the past year, I’m struck by how much I enjoyed connecting with readers and other writers here. It’s (almost) taken the place that Twitter used to hold in my heart. I am grateful to every one of you for reading my thoughts and for sharing yours (and of course, a special thanks to paid subscribers!)

Whether an arc or a circle, whether growth or mastery or unrest or destruction, may your 2024 take the shape you most desire!

Discussion Section

Does Molly’s cycle of years resonate for you?

What narrative shapes do you connect with in what you consume, and what shapes best describe your experience of your own life?

Is there anything in particular you’d like to see (or read) here in 2024?

Glad to be traveling this road with you, Liz. This is a great post, by the way, with lots for me to think about in terms of story craft. The cycle is a common one -- returning where you began, with the almanac structure of the year or some other seasonal theme, such as planting and harvest. The article you cite is new to me, and I appreciate the different linear arcs it represents.

But here are a few more thoughts about story structure. I don't believe there are any gendered story forms. I'm of the Willa Cather school on this -- the form matters less than the heart of what fills it. Here's what her character Carl Linstrum says at the end of "O Pioneers!": "Isn't it queer: there are only two or three human stories, and they go on repeating themselves as fiercely as if they had never happened before; like the larks in this country, that have been singing the same five notes over for thousands of years."

I see this often with my clients. I have a method for mapping a book project that I believe will lead to a satisfying (and efficient) first draft. It follows some form of the traditional arc, but it requires everyone to answer the questions for themselves, about what the core conflict is and what the major turning points might be. That's harder than it seems, not because it requires anyone to contort themselves into someone's shape, IMO, but because it's hard to find the story that rings as true as those larks that keep singing the same five notes. Cather herself failed in her first attempt -- which is why she said that she had two "first" novels.

In that sense I might flip your title around -- it's not the shape of the story that matters, it's what breathes life into it. There are plenty of experimental forms that flop, too, because the author hasn't found a simple, true core. For instance, I have been hindered in my own memoir-in-progress because I felt that the core of that story was perpetually under attack. Now that I reclaimed my voice somewhat, and have a better sense of what the future holds, I feel more ready to listen for what that fatherhood story might be.

I think in this way, craft can't solve everything. Take a guitar, and three blues chords, and Howlin' Wolf is going to fill that simple form with a lot more power than a kid in a suburban basement (perhaps because the lived experience invented the form). The story and the song must ring true. Now I'd be curious about your thoughts on Cather's form in "O Pioneers!'? Cather liked to take inspiration from opera, too, from Wagner's Ring cycle, for instance.

And then there is the episodic, which Dorothy Parker said was unrealistic, at least as applied to humans: "It's not true that life is one damned thing after another. It's the same damned thing over and over!"