For months now, I’ve been writing about the experience of resigning my faculty position—of “unprofessoring.” But there is one aspect of my departure that I have avoided confronting, partly because it’s so painful to contemplate. When I do let myself think about it, when the reality of leaving this part of my job behind really sinks in—I can sense my eyes prickling and pressure building in my sinuses. It’s a swell of grief, felt more in the head than in the heart.

Which I guess makes sense, because what I’ll miss the most about being a professor is, in a way, all in my head. It’s not what you might expect—not the community of scholars, the amazing students, nor the witty colleagues. It’s not the intellectual freedom nor the perks of travel, though those are certainly nice. It’s definitely not meetings or emails or activity reports.

It’s a family of ten proteins encoded in the genome of the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana.

I know! It’s cheesy as hell. When I wrote that sentence, I burst into tears! How is it possible that the hardest thing for me to leave behind as I exit academia is A BUNCH OF PROTEINS? Let me draw a long, shuddering breath and try to tease things apart a bit.

The MSLs come into my life

I first started studying these particular proteins, I was a postdoc at Caltech. I was several years into it and was floundering. I was casting about for yet another project after a few failures, when a postdoc from the neighboring Rees Lab shared a recently published phylogenetic study of a family of mechanosensitive ion channels called MscS. (Mechanosensitive ion channels are proteins that mediate ion flux across membranes in response to physical forces like touch and pressure. They are extremely cool.) The paper identified ten members of this family in Arabidopsis thaliana—implying that plants might sense forces using the same mechanism as bacteria.

Others had postulated as much, and there was abundant evidence for mechanically-gated ion currents in plant cells. But no one had yet found out what genes or proteins provided those currents, so the problem was not amenable to study using molecular biology, biochemistry, or genetics approaches. Identifying the genes and proteins involved would be an incredible molecular entry point into the field of plant mechanobiology.

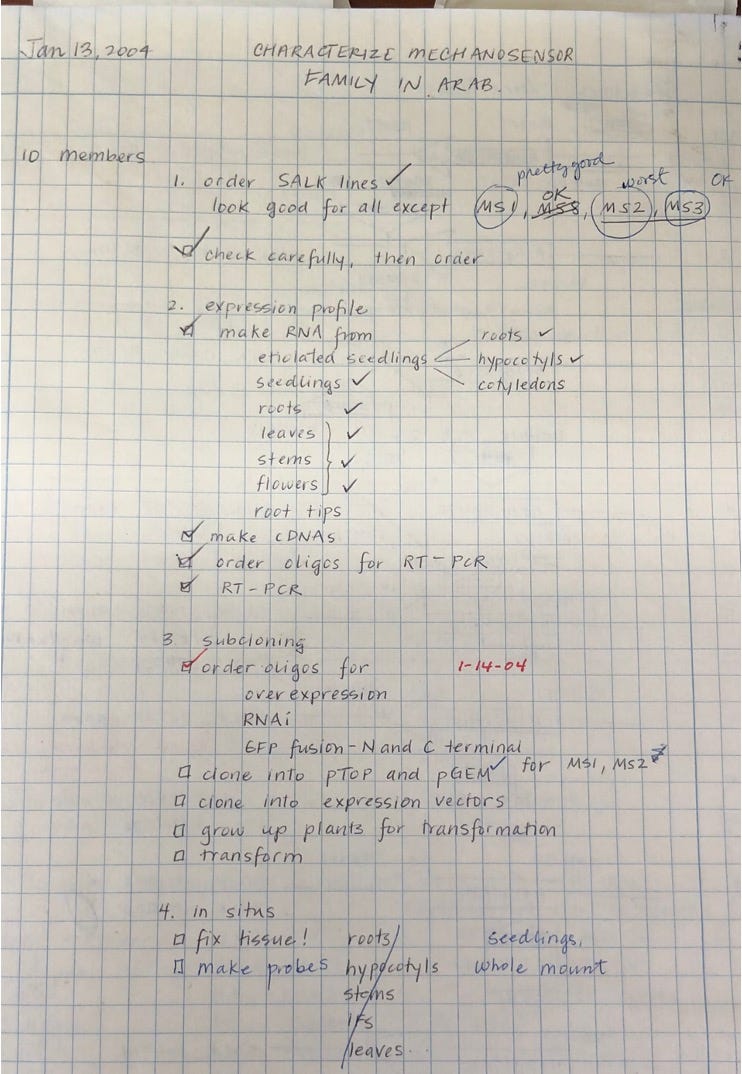

I was instantly intrigued by the possibility that these newly identified MscS family members might be providing the currents that had been measured in plant cells, and I jumped on the project. The first page in my lab notebook (shown below) named these proteins “MS” for “mechanosensor” but later I walked that assumption back and renamed them “MscS-Like” or “MSL” proteins . . . just in case they weren’t actually mechanosensitive or even ion channels at all!

My first projects on MSLs got me a tenure track job, and the study of these proteins formed the basis of my lab’s research for almost twenty years. The 10 MSLs went from being just gene numbers with modest similarity to interesting bacterial genes in 2004, to established mechanosensitive ion channels with known structures and biophysical, organellar, cellular, and organismal functions by 2023. And it was never “same in plants as bacteria”. Studying the plant MSLs—and how plants adjusted to their absence—continued to provide all kinds of plant-specific insights and understanding.

It’s all in my head

When I wrote above that “what I’ll miss the most about being a professor is, in a way, all in my head”, I don’t mean that these channels only exist in my imagination or that we made up any of our data. Obviously. I am rather referring to the fact that my affection for them feels tied to the ways I have pictured them in my mind, and the ways I’ve developed an emotional relationship to them.

Early on, I visualized MSLs as circles or the PowerPoint lozenges that biologists often use to represent molecules and protein complexes. In 2020, Peng Yuan’s lab solved the structure of MSL1 in both the open and closed states. I will never forget seeing this video illustrating the proposed atomic movements to create a channel opening. It was a moment of vindication, as we’d proposed some aspects of the channel. But mostly I felt awe and recognition, like meeting your nephews for the first time. You knew they existed, but now you can see them! It was both a revelation and confirmation.

A feeling for the organism

So, the MSLs gave me a career and something to be curious about—and I’m grateful for both. But my sadness about leaving the MSLs isn’t just about leaving something that that served me. It’s about leaving something that I love, full stop.

In her biography of McClintock, A Feeling for the Organism, Evelyn Fox Keller paints a portrait of a woman with a particularly close relationship to her research organism. McClintock, who was awarded the Nobel prize in 1983 for discovering transposition in maize, said,

“I start with the seedlings, and I don’t want to leave it. . . I know every plant in the field. I know them intimately, and I find it a great pleasure to know them.”

Keller’s main thesis is that McClintock’s emotional connection to her plants was a key aspect of her genius, and this relationship allowed her to see how maize transposons jumped around the genome, creating patterns of kernel color in the ears. Without an “intimate knowledge” of her plants, Keller argues, McClintock would not have had Nobel prize-worthy insights into their genetics.

Now, I absolutely resonate with McClintock’s idea of pleasure at knowing a research subject. I feel fond, attached, and protective of the MSLs. But I wouldn’t say that my “feeling for the proteins” led to any special understanding of MSLs, or of mechanobiology in general. I was wrong as often as I was right about what MSLs might be doing in plants and how they might go about it. But my appreciation for these proteins as entities of their own kept me motivated and engaged in research for two decades. McClintock had “intimate knowledge” of her plants and their genes; I think I had an “intimate attachment to” or “intimate investment in” my MSLs.

I never felt protective of MSLs in the sense of wanting to have them all to myself—in fact I often wished that others would work on them more. But I recall feeling protective of their dignity and feelings—like you would a child who was dealing with a bully at school. A famous plant electrophysiologist once told me that he had looked at the MSLs and they didn’t seem interesting to him—so it was okay for me to keep on studying them (this was about 10 years into it for me). I was so indignant—on their behalf as well as mine!

The perfect gift

Right before I left St. Louis in December, postdocs Josh and Ivan gave me two amazing woodcuts as a goodbye gift (see below). These woodcuts artfully illustrate the processes and model plants we studied and published on in the Haswell Lab. Normally I would post such a gift on social media immediately, both to celebrate the thoughtfulness of the gift-giver and to brag about my great lab members. But this gift was like a dagger to the heart of what I will miss most about my faculty position, and I could barely squeak out a thank you, much less compose a post about it.

But now with a little distance, I can say that these woodcuts truly were the perfect gift. Leaving my research and my beloved MSLs is one of the deepest wounds of my departure, and I think I will always be a little sad when I think about them. It helps to know that Ivan is carrying on with some of this work in his new position at University of Minnesota, and that Josh will be continuing on with related work in the Dixit Lab. Maybe if I think of the MSLs as pets going off into the world to have new adventures with other investigators, it will help.

I’ve tried to wrap this essay up a number of ways, but nothing feels quite right. I think that probably reflects where I am in the process of extricating myself from academia—we have one last MSL paper to work on so I haven’t really left it all behind yet. And these proteins were such a huge part of my professional life and my intellectual engagement, they took up so much space in my head, that it’s only natural to take some time to re-arrange the furniture up there.

Discussion Section

What do you think about the idea of having a “feeling for the organism/cell/protein/gene?” Is this a recipe for anthropomorphizing? Or just the way some of us connect with our research topics?

I knew this would make me tear up! Mostly on your behalf because I know what they have meant to you all these years. That notebook page is legendary. I had the pleasure of working on MSLs with you during the middle years and I miss them, too.

This one really resonated! I rarely search Pubmed these days, but when I do it's always `pho85`.... I think that a big piece of it for me is all the things that I still didn't know about them, even after several years of study. It's like that nephew you've finally met, but then goes off into the world never to be heard from again. Or a puzzle you put together just one corner of. What other capabilities and jobs do those proteins have that I never learned enough to even guess at, let alone know? You know?