Five reasons why we should stop advising faculty to “just say no”

tl;dr: it perpetuates inequality and devalues service

This is the first installment in a new occasional series that I’m calling “Bad Academic Advice.”

One perennial piece of advice for struggling faculty that has recently resurfaced is to “just say no” to service requests. Today I want to discuss why we should throw this advice into the shredder along with “avoid interdisciplinary work”, “let your work speak for itself”, and “get your wife to type your manuscripts”.

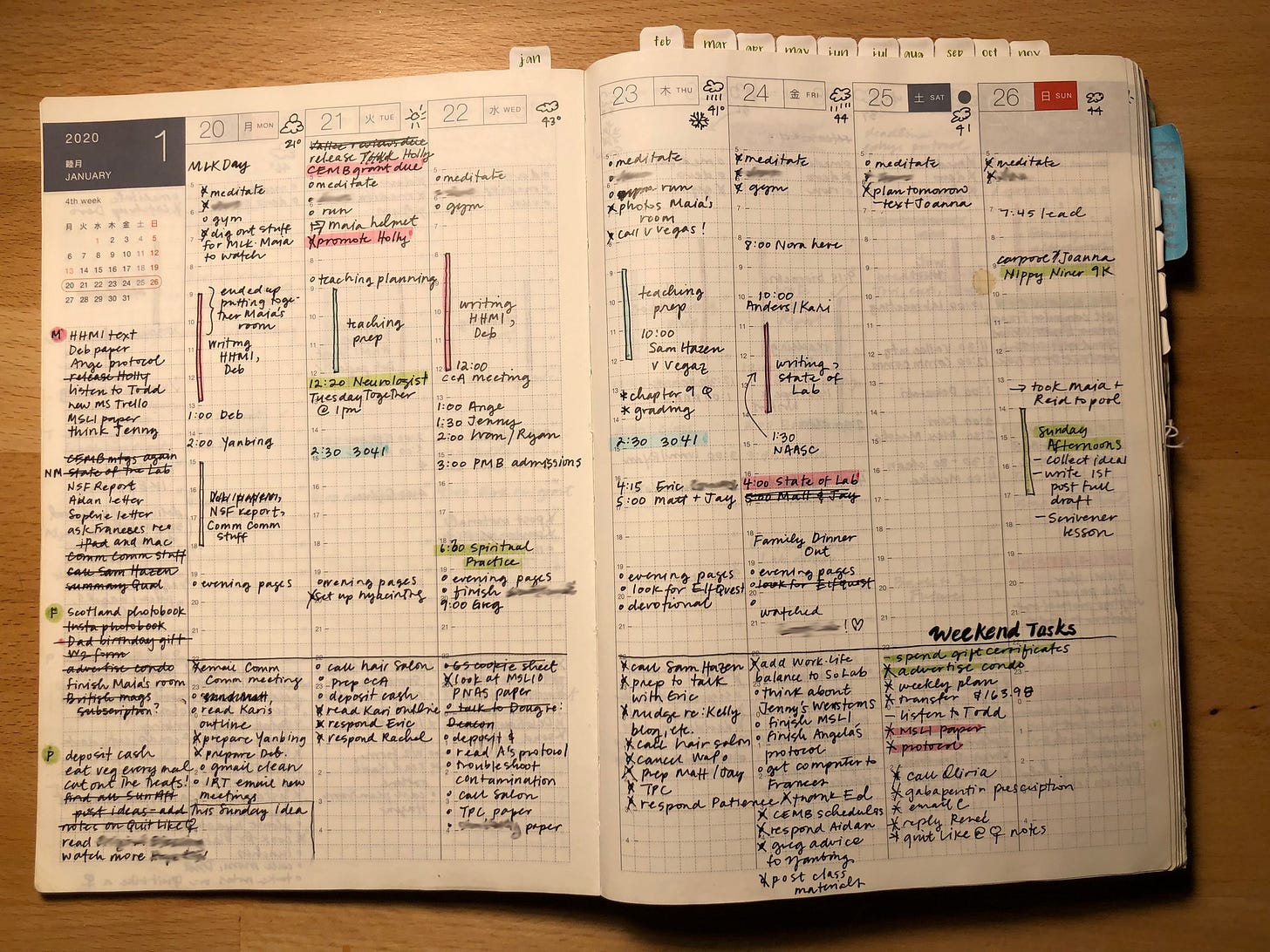

It’s true, most faculty are beyond overwhelmed with the many, many obligations associated with teaching, research, service, outreach, and administration. I’ve written about the unsustainable workload and the multiple roles required to do the job of a faculty member elsewhere. Managing one’s time and responding to requests for that time is a major part of every faculty member’s life.

Let me be clear: I am NOT recommending that junior faculty should say “yes” to every request that lands in their inbox. But dealing with the overwhelming number of tasks and obligations and opportunities that come your way as a junior faculty member is way more complicated than just saying no to some of them. Here are five reasons why I despise the blanket advice to “just say no”:

1) Almost every request is an opportunity of some kind.

The thing is, there is almost always some advantage, no matter how tiny, to saying “yes” to service. Some benefits are obvious: agree to review a paper and get to see what is new in your field, write a commentary on someone else’s paper and get your name in front of the editors of aspirational journals. But, as some have pointed out, sometimes it can be hard to know at the outset what kind of bang you’ll get for your service buck.

My strategy (if you can call it that) was to say yes to as much as I could personally tolerate. Career wise, it was a great move—I’d sit on a career panel and then be asked to give a seminar. I’d organize a meeting and then meet potential collaborators or folks who would invite me to write a review article, or who might be a reviewer for my papers or grants. The benefits of exposure through service were huge, especially right before tenure. But this “strategy” almost killed me as a person, wife, and mother. No one can do everything, all the time, without paying a big price somewhere else.

Which, of course, brings us right back to the advice to “just say no.” But,

2) Saying no has different consequences for different people in different environments.

The identity of a faculty member influences both what they are asked to do, and how it plays out when they accept or decline. When a young faculty member, a woman, or a minoritized individual declines an invitation or a request, it is often viewed differently than when a senior majoritarian does the same. The pressure to serve is both unevenly applied, and saying no has a different effect, depending on who is asking, what they are being asked to do, and who is being asked.

How “just saying no” is received can also differ depending on the culture of a department or institution. In departments like my own, being a service-oriented team player is highly valued, and perceived selfishness (or self-protection, depending on your view) can hurt one’s reputation and opportunity for advancement. In other departments, the opposite is true, and doing a lot of service reads as being unserious or too distractible.

It can be hard to win the game of “guess what will matter the most to the folks who will evaluate me”. When I came up for tenure, I was on a number of national and international steering committees, was organizing scientific meetings, and so on. It felt like a lot of service to me at the time. But my department communicated their disappointment that I wasn’t serving them or the university in the same way (serving on search committees, helping recruit undergraduates, and so on). So, even though I was saying a lot of yeses, I’d declined some of the service that was most valued by my department.

The thing is,

3) Not all faculty activities are valued in the same way and approaching them as a choice creates an opaque hierarchy.

The advice to “just say no” is usually only meant for service tasks—sitting on committees or taking on undergraduate researchers or organizing meetings—activities that typically do not count for much during promotion or tenure evaluations. But these activities are important, they create community and keep the life of the university running. And they are also the things that many faculty love and care about. By recommending faculty “say no” to service, we continue to devalue this work.

And, at the end of the day,

5) These things still have to get done.

It’s true, saying “no, I don’t want to serve on that search committee” keeps it off your desk and out of your calendar. But now who will serve on that search committee? The job will now fall to someone who doesn’t feel like they can say no, or the person who already has so much to do that adding another thing doesn’t make much of a difference.

After I got tenure, I started blocking off the morning to do “my” work. That was when I had the mental energy to tackle the most challenging edits or most demoralizing response to reviewers. Blocking this time off worked great for me. But it made the organizers of every committee I was on, including graduate students trying to schedule thesis committee meetings, work SO HARD to find times to meet. I felt guilty about this at the time and now feel even worse about it.

So how do we equitably distribute service work, especially when everyone in a department is working so hard at so many things?

5) Saying no perpetuates the individualization of the problem of overwork.

Here is where I’m going with all of this:

Instead of telling overwhelmed faculty to say no, why aren’t we telling university leadership to stop asking so much?

Junior faculty, especially, are victims of the system, and telling them to manage the overwhelm by declining a few activities here and there is like telling women to manage the threat of rape by wearing longer skirts. Rather than continuing to play “hot potato” with service tasks that are undervalued and for which faculty do not have enough time, maybe university leadership should stop asking faculty to do so much??

And really, is this really the culture we want to perpetuate—one where we are all asked to do too much and then we all tell each other to say no to most of it? If those with power to say “no” to service tasks do so, and everyone else has to just figure it out, university and community service becomes a matter of personal stamina and individual privilege when it should be something that is handled structurally.

The escalation of committees and strategic plans and task forces and compliance training and paperwork and general student-centered razzmatazz isn’t going to stop until faculty put their collective feet down and COLLECTIVELY “just say no”.

I’m so interested in your take on this. And consider sharing it with a junior faculty member in your life!

Discussion Section

What has your experience with this advice to “just say no” been?

Are there other aspects to this advice that I’ve missed?

Most of all I'd like to see more transparency about department/college/university level service needs and who has stepped in to meet them. A giant public spreadsheet if you will. I once asked my chair to create such a list for our department. When I finally saw it I was SHOCKED at how unevenly the service tasks were assigned. I'd always considered service important, but obviously (and sadly) most of my colleagues do not. It wasn't hard to start saying no once I'd seen the data.

In my recent performance review (happens every five years at my college, post tenure) where I spelled out how many facets of my workload have doubled in the last five years (e.g., advising, class size, # new preps, committee work, etc - I'm in a liberal arts college, btw) my Associate-Dean suggested .... wait for it ... that I start saying "no". In a student-focused era where retention matters for budgets, I was told to say no to students' faces when they asked for [fill in the blanks]. Wow, right? That's horrible. As I type this I am seeing emails pop-up from students asking me to over-ride my course caps because they *need* my class that's closed. Sigh.

So you can imagine that I read your post with interest and in solidarity. This "just say no" solution to the problem of overwork is victim blaming. As you and others remark, it deflects from the real heart of the issue that drives faculty overwork and burnout -- it's the system's fault, not ours. As another reader has commented, we do not cause our own burnout! And self-care isn't going to solve our burn-out problems. We are driven to excel at our work, and our motivations are complicated (I, like you, often romanticize my grad school days...). It is a near-intractable problem.